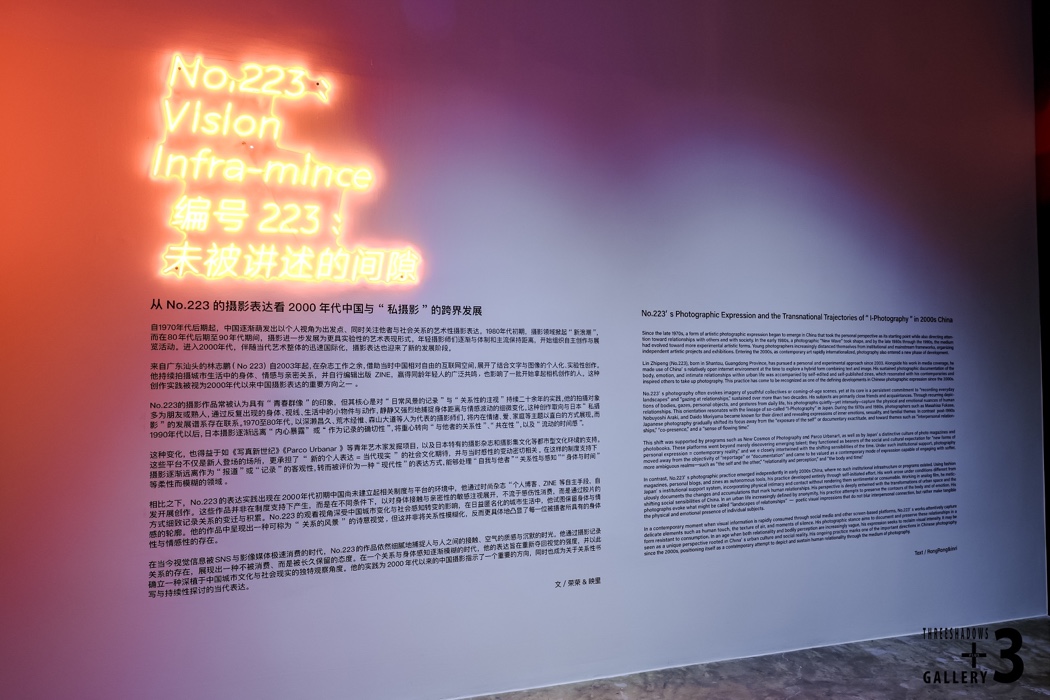

从No.223的摄影表达看2000年代中国与“私摄影”的跨界发展

文_荣荣&映里

自1970年代后期起,中国逐渐萌发出以个人视角为出发点、同时关注他者与社会关系的艺术性摄影表达。1980年代初期,摄影领域掀起“新浪潮”,而在80年代后期至90年代期间,摄影进一步发展为更具实验性的艺术表现形式。年轻摄影师们逐渐与体制和主流保持距离,开始组织自主创作与展览活动。进入2000年代,伴随当代艺术整体的迅速国际化,摄影表达也迎来了新的发展阶段。

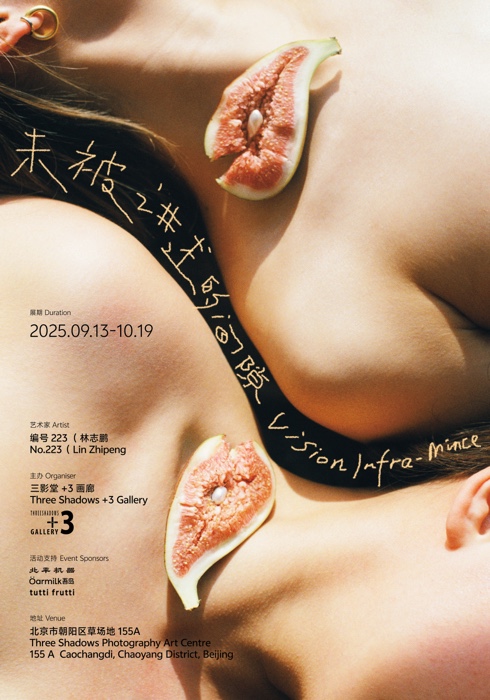

来自广东汕头的林志鹏(No.223)自2003年起,在杂志工作之余,借助当时中国相对自由的互联网空间,展开了结合文字与图像的个人化、实验性创作。他持续拍摄城市生活中的身体、情感与亲密关系,并自行编辑出版ZINE,赢得同龄年轻人的广泛共鸣,也影响了一批开始拿起相机创作的人。这种创作实践被视为2000年代以来中国摄影表达的重要方向之一。

No.223的摄影作品常被认为具有“青春群像”的印象,但其核心是对“日常风景的记录”与“关系性的注视”持续二十余年的实践。他的拍摄对象多为朋友或熟人,通过反复出现的身体、视线、生活中的小物件与动作,静静又强烈地捕捉身体距离与情感波动的细微变化。这种创作取向与日本“私摄影”的发展谱系存在联系。1970至80年代,以深濑昌久、荒木经惟、森山大道等人为代表的摄影师们,将内在情绪、爱、家庭等主题以直白的方式展现。而1990年代以后,日本摄影逐渐远离“内心暴露”或“作为记录的确切性”,将重心转向“与他者的关系性”、“共在性”,以及“流动的时间感”。

这种变化,也得益于如《写真新世纪》《Parco Urbanart》等青年艺术家发掘项目,以及日本特有的摄影杂志和摄影集文化等都市型文化环境的支持。这些平台不仅是新人登场的场所,更承担了“新的个人表达 = 当代现实”的社会文化期待,并与当时感性的变动密切相关。在这样的制度支持下,摄影逐渐远离作为“报道”或“记录”的客观性,转而被评价为一种“现代性”的表达方式,能够处理“自我与他者”“关系性与感知”“身体与时间”等柔性而模糊的领域。

相比之下,No.223的表达实践出现在2000年代初期中国尚未建立起相关制度与平台的环境中,他通过时尚杂志、个人博客、ZINE等自主手段,自发开展创作。这些作品并非在制度支持下产生,而是在不同条件下,以对身体接触与亲密性的敏感注视展开,不流于感伤性消费,而是通过胶片的方式细致记录关系的变迁与积累。No.223的观看视角深受中国城市变化与社会感知转变的影响,在日益匿名化的城市生活中,他试图保留身体与情感的轮廓。他的作品中呈现出一种可称为“关系的风景”的诗意视觉,但这并非将关系性模糊化,反而更具体地凸显了每一位被摄者所具有的身体性与情感性的存在。

在当今视觉信息被SNS与影像媒体极速消费的时代,No.223的作品依然细腻地捕捉人与人之间的接触、空气的质感与沉默的时光。他通过摄影记录关系的存在,展现出一种不被消费、而是被长久保留的态度。在一个关系与身体感知逐渐模糊的时代,他的表达旨在重新夺回视觉的强度,并以此确立一种深植于中国城市文化与社会现实的独特观察角度。他的实践为2000年代以来的中国摄影指示了一个重要的方向,同时也成为关于关系性书写与持续性探讨的当代表达。

Transcultural Developments in 2000s Chinese Photography: The Case of No.223 and the Legacy of Private Photography

Text_Rongrong&Inri

Since the late 1970s, a form of artistic photographic expression began to emerge in China that took personal perspective as its starting point while directing attention toward relationships with others and society. In the early 1980s, a photographic “New Wave” emerged, and by the late 1980s through the 1990s, the medium evolved toward more experimental artistic expression. Young photographers increasingly distanced themselves from institutional and mainstream frameworks, organizing independent production and exhibition activities. Entering the 2000s, as contemporary art rapidly internationalized, photography also underwent a new phase of development.

Lin Zhipeng (No.223), born in Shantou, Guangdong Province, began developing a personal and experimental approach from 2003 onward, alongside his magazine work. He utilized the relatively open internet environment in China at the time to explore a hybrid method that combined text and image. His sustained photographic documentation of the body, emotion, and intimate relationships within urban life was accompanied by self-edited and self-published ZINEs, which resonated with his contemporaries and inspired others to begin photographing. This practice has come to be recognized as one of the representative developments in Chinese photographic expression since the 2000s.

No.223’s photography often evokes imagery of youthful collectives or coming-of-age scenes, yet at its core lies a persistent commitment to “recording everyday landscapes” and “gazing at relationships,” maintained consistently for over two decades. His subjects are primarily close friends and acquaintances, and through recurring depictions of bodies, glances, small personal objects, and gestures of daily life, his works delicately and sometimes intensely reflect the physical and emotional nuances between people. This orientation resonates with the lineage of so-called “private photography” in Japan. During the 1970s and 1980s, photographers such as Masahisa Fukase, Nobuyoshi Araki, and Daido Moriyama were known for their direct and revealing expressions of inner emotions, love, and familial themes. In contrast, post-1990s Japanese photography gradually shifted its focus away from “exposure of the self” or documentary exactitude, and toward themes such as “interpersonal relationships,” “co-presence,” and a “sense of flowing time.”

This shift was supported by platforms such as New Cosmos of Photography and Parco Urbanart, as well as by Japan’s unique culture of photo magazines and photobooks. These venues were not simply talent showcases but served as socially and culturally charged stages for what was perceived as “new personal expression = contemporary reality,” closely intertwined with changes in the sensibilities of the time. Under such institutional support, photography moved away from objectivity in the form of “reportage” or “documentation,” and came to be valued as a “contemporary” mode of expression capable of engaging with softer, more ambiguous realms―such as “the self and the other,” “relationality and perception,” and “the body and time.”

In contrast, No.223’s photographic practice emerged independently in early 2000s China, where no such institutional infrastructure or platforms existed. Utilizing fashion magazines, personal blogs, and ZINEs as autonomous tools, his expression took form through self-initiated effort. His work was created under different conditions from Japan’s institutional support system and incorporates physical intimacy and contact without rendering them as sentimental or consumable. Through analog film, he meticulously documents the changes and accumulations of human relationships. His gaze is deeply entwined with the transformations of urban space and shifting social sensibilities in China. In an urban life increasingly characterized by anonymity, his practice attempts to retain the outlines of the body and emotion. His photographs evoke what might be called “landscapes of relationships”―poetic visual impressions that do not blur interpersonal connection, but rather make tangible the physical and emotional presence of individual subjects.

In a contemporary moment where visual information is rapidly consumed through social media and screen-based media, No.223’s works attentively capture delicate elements such as human touch, the texture of air, and silent time. His photographic stance aims to document and preserve these relationships in a form that resists being consumed. In an age where both relationality and bodily perception are increasingly vague, his expression seeks to reclaim visual intensity. It can be evaluated as a unique perspective rooted in China’s urban culture and social reality. His ongoing practice signals one of the important directions in Chinese photography since the 2000s, positioning itself as a contemporary attempt to describe and sustain human relationality through the medium of photography.